I’ve recently been reading Shakespeare’s Macbeth out of order. I listed the scenes on a spreadsheet, numbered them from 1 to 29, and I have asked a random-number generator to choose which scene I will tackle next. There’s a method to this madness—and a result, as well—a piece of music I’m composing. If any of that sounds interesting, read on.

Recently, I’ve been starting newsletter posts that get derailed–by life, by work, and by the fact that people I’m writing about keep dying. I’d started a long post about comedian/mathematician Tom Lehrer, only to have him pass away while it was still on the drawing board. I then started a new newsletter entry with the line, “I can’t remember when I first encountered theatrical impresario Robert Wilson,” only to open up The New York Times and see his obituary.

Makes one a little nervous to write about anyone.

But I’m circling back to Robert Wilson today, because his work is so fundamental to what I’ve been working on recently.

When I’m not writing/lecturing/leading walking tours of New York City history, I keep myself busy on a bushel of other projects. Someone once told me that the way to overcome writer’s block is always to have a few projects going simultaneously. I take this to extremes, and I usually keep over a half dozen different works in various media simmering at the same time. Right now, what’s taking up most of my time is a suite of music based on Shakespeare’s Macbeth.

As I said, I can’t remember when I first encountered Robert Wilson, but it was probably via his collaboration with Philip Glass on the opera Einstein on the Beach or David Byrne’s score for The Knee Plays. Certainly, the first time I saw his work on stage was at the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) in the 1990s, when he collaborated with Lou Reed and Darryl Pinckney on Time Rocker, an adaptation of H.G. Wells’s The Time Machine.

I’d been aware of Wilson’s two previous pieces at BAM, Black Rider and Alice, written in collaboration with Tom Waits, but I had a strange aversion to Waits back in the 1990s,1 so I didn’t venture out to Brooklyn to see either one. But Lou Reed was one of my childhood heroes—I wore out my cassette of Transformer—and who doesn’t love H.G. Wells,2 so we headed out to Brooklyn to see the show.

I hadn’t been raised with much avant-garde theater on the menu—unless you count Monty Python (or, I realize now only in retrospect, the original Planet of the Apes franchise). I watched a lot of Shakespeare when I was too young to understand it; I auditioned for The Music Man when I was ten years old (I didn’t get it). I listened to Hair a lot (when I was also too young to understand it). I started reading more structurally challenging work in high school, from Sophocles to Brecht, Stoppard, and Christopher Durang, but none of those quite prepared me for this:

Time Rocker isn’t the greatest musical ever written.3 But Wilson and Reed’s fusion of costume, sound, lyrics, and movement was revelatory to me. (Wilson was highly adept at using light as a medium in itself. As he told Dance magazine,

[I appreciate]…Hollywood portraits of the early 30s and those from Germany in the 20s where light performed as an actor, where every movement, every second was lit and sculptured, allowing us to hear and see more readily and intensely…. Light in my work functions as a part of an architectural whole. It is an element that helps us hear and see, which is the primary way we communicate. Without light, there is no space.

And what does any of this have to do with Macbeth?

While I saw many Robert Wilson creations after that night at BAM, the most memorable was Hamlet: A Monologue, which I think took place at Lincoln Center in the year 2000. As Wilson noted

People say that I’m not interested in words…so some years ago I said, “Okay, I’ll do Hamlet….” I did it as a monologue, a kind of dream memory of the entire play. I restructured the text, beginning seconds before Hamlet dies. So the work is seen as a flashback, with Hamlet speaking the text of Ophelia, Gertrude and all the other characters. The play really takes place in Hamlet’s mind.

As someone who’d read and seen Hamlet a dozen or more times when I saw the monologue, I was immediately enrapt by the idea of taking the words—some of the most famous in the English language—and shearing them from their context. Scenes are played out of order, soliloquies are repeated, chopped up, and repeated again. Wilson privileged the text as a thing of beauty in itself, divorced from the machinations of the play’s plot and structure.

Fast forward 25 years, and here I am, using a Wilsonian strategy for reading Macbeth.4 I wouldn’t necessarily suggest this approach if you don’t know the play well, but I feel it allows each scene to have its own meaning. Characters appear and disappear with little rhyme or reason, but the text shines. The rhymes are the reason, if you will.

Now, my project is more complicated than just reading the play. I’m also attempting to distill each scene into a movement of a thirty-piece Macbeth suite. I find that approaching the play out of order frees me from the shackles of trying to interpret any given scene solely through the lens of its plot, allowing me instead to focus on the emotional impact of the dialogue. It also means, by and large, that I’m never composing two scenes that will stand next to each other in the finished piece, so I avoid what is a common pitfall for me of writing too much music that sounds the same.

My classical music antecedents are mostly modern, including Philip Glass, John Cage, Meredith Monk, Max Richter, and Steve Reich, as well as the ambient music of artists like Brian Eno, and the soundtrack work of Hans Zimmer and Ludwig Göransson.

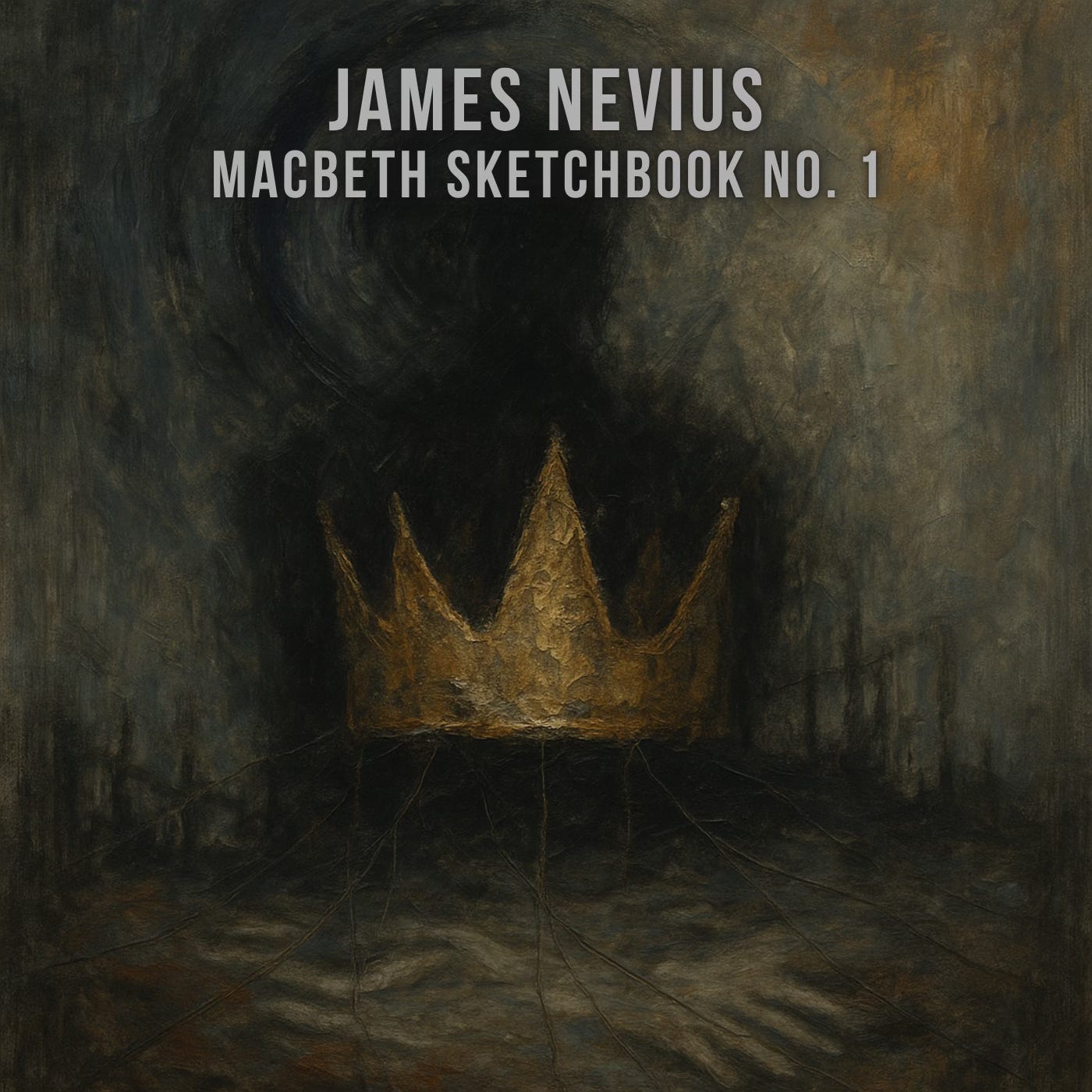

I recently reached the halfway mark in my ongoing work and released the first 16 tracks5 as an album called Macbeth Sketchbook No. 1. I refer to it as a "sketchbook" because I tend to work quickly and loosely; all of these movements will be further refined. At the very least, they’ll be remastered; in some cases, they will be completely reconfigured.

Right now, the album is only available for purchase on Bandcamp at jamesnevius.bandcamp.com.

If you prefer to stream, I’ve got you covered on most major services:

If you are interested in the story behind each piece, definitely go the YouTube route, as there’s an explanation of each movement and a description of how it fits into the overall plot of Shakespeare’s play.

(Note: the songs on these playlists are arranged in the order they appear in the play, not in the order in which they were composed.)

…and, in other news…

Below this point are links and musings exclusive to paid subscribers, including some Manhattan real estate porn, the connection between the Beatles and John Cage, news and notes on my Dutch forebears, and more.

Subscribe today!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to History Will Teach Us Something to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.